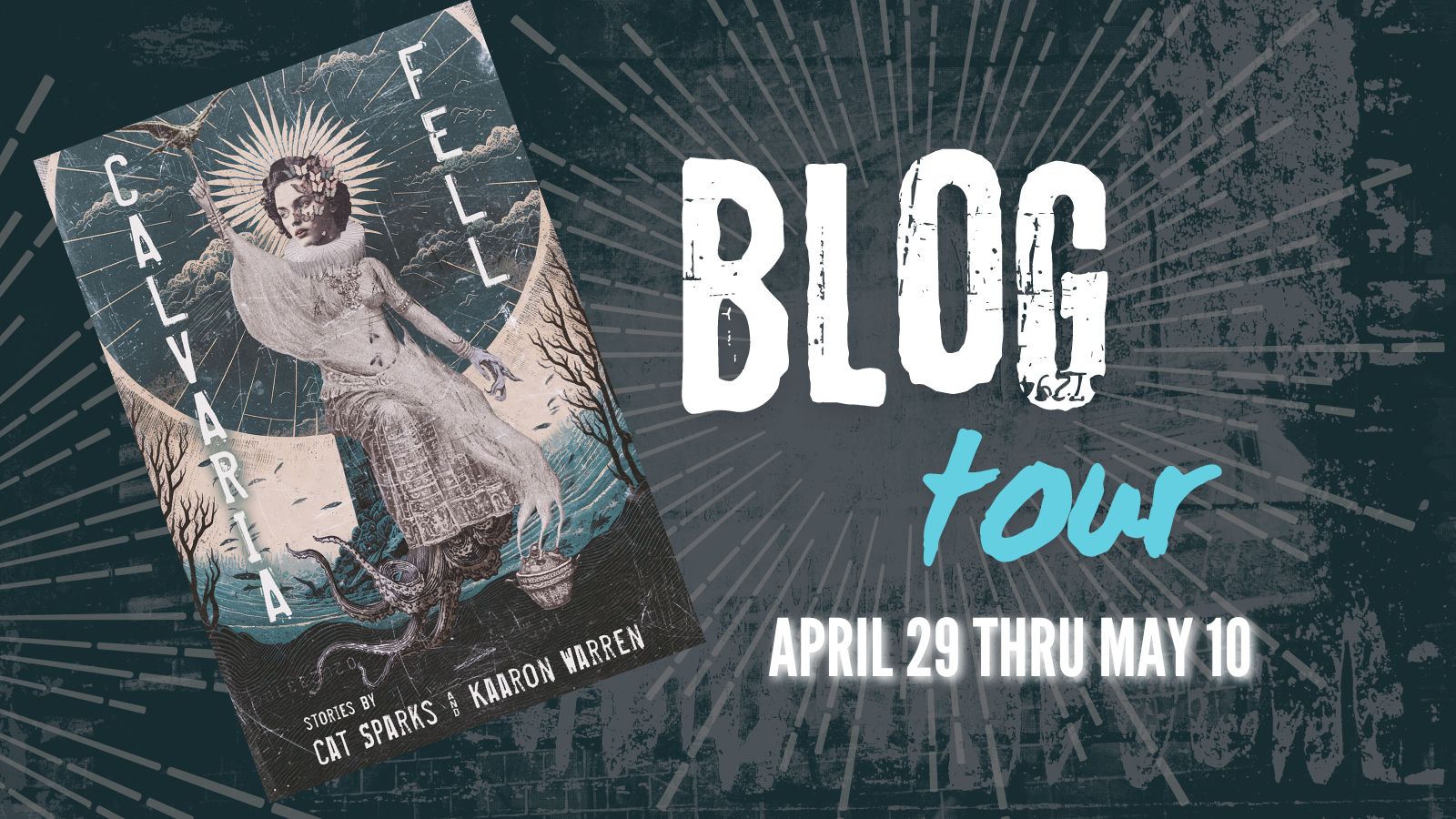

CALVARIA FELL: STORIES by Cat Sparks and Kaaron Warren

Calvaria Fell is a stunning collaborative collection of weird tales from two acclaimed authors, Kaaron Warren and Cat Sparks. It features previously published stories from both authors, along with a new novella by Kaaron Warren and four new stories by Cat Sparks. The collection offers a glimpse into a chilling future world that is similar to our own. Readers will be drawn into experiences at once familiar and bizarre, where our choices have far-reaching consequences and the environment is a force to be reckoned with. The title of the collection tethers these stories to a shared space. The calvaria is the top part of the skull, comprising five plates that fuse together in the first few years of life. Story collections work like this; disparate parts melding together to make a robust and sturdy whole. The calvaria tree, also known as the dodo tree, adapted to being eaten by the now-extinct dodo bird; its seeds need to pass through the bird’ s digestive tract in order to germinate. In a similar way, the stories in Calvaria Fell reflect the idea of adaptation and the consequences of our actions in a changing world.

BUY LINKS: Meerkat Press | Bookshop.org | Amazon

ABOUT THE AUTHORS:

Kaaron Warren has been publishing ground-breaking fiction for over twenty years. Her novels and short stories have won over 20 awards, from local literary to international genre. She writes horror steeped in awful reality, with ghosts, hauntings, guilt, loss, love, crime, punishment and a lack of hope.

My Book Review: Coming Soon

GIVEAWAY: $25 Meerkat Press Giftcard

GIVEAWAY LINK: http://www.rafflecopter.com/rafl/display/7f291bd841/

The Emporium

Kaaron Warren

Chapter One

Things improved once the mattresses arrived. Before that they’d slept curled up in massage chairs or stretched out on couches that were too short for them and stained with old spills; drinks, food, body fluids, drips from the leaking roof.

They cleared out the secondhand furniture shop of everything except the bedframes, which mostly rested up against the wall.

That area had been a mess, anyway, filled with objects found over many years, the “miscellaneous,” items no one knew what to do with. It was stacked dangerously high; boxes of picture hooks, crates of broken wineglasses, piles of true crime magazines. Things they no longer understood and could barely recognize. They moved the broken things upstairs, finding nooks and crannies in the old shops there, trying to keep some sort of order.

In the front corner of the shop, near the small register, were stacked boxes of ancient cat food. Maud said, “We should take that up to the roof. The birds might eat it if we spread it around.” The other children all agreed, so they piled it outside the shop next-door, a newsagent still stocked with ancient news and magazines. They added the true crime magazines to that collection and headed back to the furniture shop.

Marty stood with his hands covering his face, his shoulders shaking.

“Marty! What’s wrong?” Maud said. “You’ll get a mattress, don’t worry! There’s enough for everyone.”

“He’s sad about the fish,” Bean said. She was so short she could barely see over the counter, but she stretched her toes and pointed. At seven she was the youngest of the children in the Emporium and she hated that. She wanted to be old, like the rest of them. Yet she carried a sack full of soft toys and would bring them out for conversation and cuddles.

Maud looked. Revealed once all the mess was cleared away was a large fish tank. It was filthy, covered with moss and slime, with five centimeters of sludgy water at the bottom. Maud stepped closer. It stank; in the bottom were a dozen long-dead fish, their flesh mostly rotted off, their bones poking through. She sobbed as well, and that set all of them off, all of them sobbing over the starved dead fish. There was much they didn’t remember but all of them remembered the pets they’d left behind.

Carlo pressed his head up against the glass. “Which one is which, do you think? Who is who?”

“You can’t tell, once they’re a pile of bones. They won’t be able to know who’s us when we’re bones,” Julian said.

—

They dragged the mattresses onto the bedframes and laid some in the spaces in between. Bean wanted to take hers into the entrance atrium, a glass-ceilinged dome, so she could sleep under the stars. Maud said, “You’ll freeze to an ice block. Maybe when it gets warmer,” so Bean crankily dragged her mattress into the furthest corner, tucked under an old counter.

—

The children collapsed, exhausted but happy, on the mattresses. They weren’t very clean, though, so the next job was to traipse up to the first floor for new sheets and pillows. The Bedroom Bonanza store had been small but well-stocked. A lot of it had gone to customers outside (everyone preferred their bed linen unused) or in the looting, but there was one alcove the children had been saving for this occasion. They mostly used the stuff that came in through the dock in great mounds. They used the worst-stained bedclothes for other things, like an outer lining for the building as insulation, or they’d tear them up for bags of rags they’d leave outside in the delivery dock. They didn’t get much in return for the rags: a crate of yo-yos (none of them had any idea what to do with them but luckily Julian found a book and that was fun) or a box full of broken, salty crackers, stale but still good for soup, a carton of books, all the same and with the front cover torn off. That sort of thing.

Julian pushed up the roller door of the Bedroom Bonanza and exclaimed. The smell washed over all of them; damp cloth and mold.

“Oh, no!” Kate said. She was the one most looking forward to the new beds. Somehow she remembered the comfort of climbing into a freshly-made bed.

Water had leaked through. They had buckets all over the shopping center and the rhythmic plink plink of water droplets calmed some of them, annoyed others.

The walls were damp and the alcove holding the sheets was inches deep in water.

“It’ll be all right. They’re still in their plastic,” Julian said. He stepped into the smallest puddle and stretched out, passing the packages of sheets out one by one.

—

Carlo led Bean downstairs to the laundromat. It was dark; the line of high windows were dirty and cracked. The lights flickered on when he hit the switch and buzzed quietly; they would keep flickering until they were turned off.

Carlo organized the loads, saying, “I’m not doing it all.” But they knew he would. Carlo used to run the machines alone, and he’d still help when any of them forgot which buttons to push. He got tired of the state of clothes and bedding. With someone else washing it, they didn’t care about how dirty those items were. Once everyone had to wash their own, they took more care.

There were piles of washing in each corner and piled up behind the counter, way higher than the bench top. It had an odd smell, not bad exactly, but kind of meaty. Unpleasant.

Carlo timed it perfectly, filling the machines, adding soap (who knows how old, but it still smelled of soap at least) and closing the lids, then racing from one to the other pressing START. All six machines slowly filled with water and one by one most of the other children crept out. Carlo was mesmerized by the machines and their rhythm, hearing music that made him want to dance.

The machines followed one second after the other, and he spun around, click-spin rock and roll, not caring there was no one there except Bean.

“It’s okay! I know it’s loud! It’s really loud! But the good thing is we know it will stop. Or maybe I’m magic and they will stop on my command.”

Bean shook her head and giggled.

“You doubt the great Carrrlooo?” He rolled his rrrs until Bean joined in. She sat some of her soft toys on the machine and watched them vibrate.

When the machines stopped, Bean went to get the others while Carlo emptied each machine into a different basket. These were ones taken from the supermarket; the laundromat ones had fallen apart long ago or, perhaps, had been used to carry away loot when the shopping center closed suddenly.

The children weren’t sure why it had.

Carlo gave each child a basket of wet washing and they all made their way to the roof. They didn’t like to use the elevators unless they had to, for fear of being stuck between the floors. They told stories of ghosts, forever trying to get out.) The elevators worked before their time, but not since the children had been there.

There was the Very High Roof, but they rarely went up there at the top of the eight story tower.

The much bigger Lower Roof was only two floors up and was flat. The children had found ropes strung up here, with some aprons and workman’s clothes, stiff from hanging in the weather for a long time.

This was where they dried their clothes, and where they hung the freshly washed sheets and pillowcases. They pegged pillows to the line as well, hoping to air them out.

Marty had grabbed a box of the old cat food and shook handfuls out to feed the birds. There weren’t many (the manager had told them it was because the trees were too skinny) but sometimes they did come and perch on the cracked walls, perhaps on their way to elsewhere, somewhere greener. Two black birds and one that was a sickly gray came and pecked at the food, squawked, pecked again. Marty threw more and then the others did. Maud felt momentary joy in this, and she made sure everyone got a handful to toss.

For many miles around there were gray buildings, most of them less than four floors high. “Gravity Leaks,” they called it, meaning tall buildings could not be expected to stay sturdy anymore. Beyond them lay the forest. And way beyond that was the water. From the high roof you could see the trees, or at least the concept of trees, way off in the distance; sometimes Maud would go up there, just to see something green. They didn’t know what sort of trees they were.

Between the forest and the buildings, the Great Fire had laid waste to most everything. When the sun was out, you could sometimes see silvery trails through the black mess, left by people walking toward the forest, perhaps, or to the innumerable mounds that perhaps covered useful items.

Some of these items came as deliveries to the children: dinner plates, cake tins, barbeque grills, coats. Sometimes they were damaged beyond cleaning by ash and smoke, but most things they could wipe clean and sort, awaiting the next time someone needed garden chairs, or metal fence posts, or glass jars, or saucepans. Things the children didn’t always understand, or had forgotten about. Before he ran away, the manager had tried to teach them stuff about the past but they forgot so easily.

—

They made the beds and snuggled down. Maud went into the supermarket and brought back some fizzy drinks and the oldest of the potato chips. If it was a really special occasion, they’d open a fresher packet. Like the birthday they all shared, or perhaps the arrival of someone new. Maud set her suitcase beside her mattress, laying it down flat so she could use it as a table or as a shelf. The others followed suit; they often followed Maud’s ideas. Maud’s suitcase was brown leather covered with stickers.

“No one is very hungry for dinner after all those snacks, are they?” Julian said. He had not eaten the snacks himself; that food made him feel sluggish.

“Me me me!” Bean squealed. “Sausages!” Bean always wanted sausages.

“It’s not really dinner time yet,” Josh said. The only clocks they had were the ones in the clock shop, broken most of them, and only one, which used sunlight for power, still running. Kate could keep time by the music that played, and she was teaching the others to do so as well. They didn’t know the names of most of the songs and couldn’t understand half the words, but they all sure knew the music.

“Carry on,” Kate said. “It’s time for dinner.”

Izzy jumped up. “I’ll do it,” she said. She always did it.

There was no big oven in the kitchen, but there were salvaged burners and a toaster oven and a microwave, and with these Izzy wrought miracles. Most of the saucepans they received were only good for melting down, but they had gathered three good ones, still in their boxes, and these they used. They sometimes got fresh food delivered. Fruit and veggies. They didn’t like that too much, preferring the frozen food. The old manager used to make them eat boiled vegetables. Disgusting.

Izzy made sausages (skinless frankfurts) from the can for Bean, then a big pot of soup. Tins of asparagus soup and asparagus pieces, a can of evaporated milk, a packet of herbs, and with some crackers it was a feast. They took their bowls into the food court and sat in small groups. They didn’t always sit together but after the excitement of the mattresses, they felt like they wanted to be cohesive. There were old menus left on some of the tables, describing food long since forgotten. Sometimes they tried to cook by the menus, invent what they thought Spaghetti Carbonara was, or Eggplant Parmigiana. They’d say, What should we have for dinner, as if anything was possible.

The roof was leaking in the food court, so there were buckets everywhere. Over in the corner, one of them had a drowned rat in it. They’d all vote Julian take that away after the meal. Until then, they’d ignore it. He’d toss it over the dark side of the building. Below, a dozen cars sat rusting. This was where they threw all the dead creatures they found.

Josh gathered up the dirty dishes and dropped them down the elevator shaft. He was the first to do this when it was his turn, arguing that they had thousands of dishes so why waste time washing them? Now they all did it.

—

Bean was the first to jump from mattress to mattress, squealing with delight and the others soon followed, hollering and screaming with laughter as they jumped from one end of the large showroom to the other. Someone put a CD in the boombox. They sorted most sound equipment for sale but held one back every now and then when another broke. The broken ones were sold for parts and elements, like all the phones were. Carlo had the job of pulling them apart. Each of them took responsibility for something. They had to turn it up loud to drown out the playlist, but this way at least they felt they’d chosen what to listen to.

If the manager had been there he would have said, “If you’ve got enough energy for bouncing around, you’ve got enough energy to work.”

But he had long since disappeared. He’d left with pockets full of salvaged (stolen) coins. Maud kept a list of all the things that came into the Emporium, as well as a tally of what went out, so she and the others knew what coins he’d taken. A lot of them were scrounged from the wishing well, but everything that came in was checked for money. He’d given them all lessons in value, but Maud was only fourteen then and remembered very little. That was a long time ago. She was fifteen now and thought she’d be better at learning if someone wanted to try. He’d stopped teaching them things; Carlo said it was because he didn’t want them to know the value of what he was stealing, and that seemed as likely as anything else. Although he was very tired, always, so tired. He didn’t say goodbye when he left but he did leave a map for them, directions to the stash of small, sealed cakes, dozens of boxes, that he was saving for a special occasion. They were stacked carefully on the third floor, in If It Fits, mixed in with the shoe boxes full of footwear that didn’t, in fact, fit.

They hadn’t seen that manager in a long time. It took a while before anyone outside the Emporium noticed. Julian took charge of the orders and Maud (after Rachel left to go to medicine school) was the boss of things delivered, so they didn’t need a manager. It was only when the nurse came in to do the immunizations that the manager’s disappearance was revealed.

Gardens of Earthly Delight

Cat Sparks

“Them two in the corner. The ones wrapped up in silver. Those would make a lovely pair of elves.”

The broker squints through the floating detention center’s musty ambience, searching through the mess of huddled forms. Forty bodies jammed into each cage, barely stirring from heat stress and exhaustion. “Might do,” he says, sniffing loudly, wiping his nose on his damp stained sleeve. “How much?”

The guard names a figure and the broker laughs. “They’re flotsam off the Risen Sea, not royalty or richling lah-de-dahs! I’ll give you sixty for the both, providing they don’t got nothing worse than scabies.”

“Eighty,” says the guard, crossing his arms. “Their bloods are clean. My cages are the cleanest on this barge!”

“So you reckon,” says the broker, patting down his pockets for his purse. “Seventy—and that’s my final. Take it or you can bugger off.”

The men bump elbows to seal the deal and a fold of grimy notes passes hand to hand. The guard unclips a torch from his belt, light-spears the huddled forms until they squirm. “You two—get yerselves moving if you know what’s good for ya,”

Thermal blankets shiver, disgorging tangled arms and legs. Thin brown bodies shielding eyes from the bright beam, nudging their way to the cage’s single door. Stepping around the ones who can’t or won’t budge.

Silver scrunches as the boy clasps the blanket against his chest.

“Ed here’s got an employment opportunity,” says the guard.

“What kind?” says the girl.

“Well, aren’t we the picky ones. A one-way ticket out of this shithole and ’asides—you won’t be getting nothing better. Barge can only hold so many. Pass this up and you’ll end up wherever yer sent.”

He sniffs . . . wherever yer sent being well understood as code for over the side. The fetid harbor holds a lot of secrets.

Crinkling thermal masks, covert whispers. “We stay together,” the girl states. “We must not be separated.”

The guard dips the beam, slings a glance at the broker who nods enthusiastically. “Oh yeah, they’re definitely a set. No question. Madame will take ’em both, for sure. No worries.”

He leans closer. “Madame takes her job real serious. Reckon she used to be one of your lot. She’ll see you straight and have yer back. Takes a hefty cut of coin but she’s worth it all.”

The guard waves over armed reinforcements before punching in a complicated door code. Dulled detainees groan and shift, taking an interest in proceedings, rattling wires and slinging slurs and insults.

The guard grabs the girl’s thin arm to yank her through the doorway. The boy leaps after, abandoning the blanket to a sea of grabbing hands as the heavy steel cage door is slammed and bolted.

—

Madame raises an eyebrow when she learns how far the twins have come. Nobody travels far these days. Not like in the Before time when people wandered free and easy to far-off lands with names and edges, their borders crossed with a minimum of fuss and barter.

She frowns but doesn’t contradict. Madame Bastarache didn’t get to be uncontested Grandam of Calvaria Estate for decades without knowing when and why to listen.

“Give us yer names, then.”

“I’m Pearl,” says the girl, standing straight, “and he is Kash.”

“You’ll make a simply adorable faery duo, sister Pearl and brother Kash. Is faeries what you had in mind?” Madame eyes them over, her eyelids thickly painted petal pink. “You’re skinny enough for faeries, tis for sure. Course you know you’ll have to stay that way. And then there’ll be the wing implants. Some folks don’t take too well to that kind of thing.”

“We will take to it,” says Pearl.

Kash nods.

Madame beams, rouged cheeks shimmering with glitter. “Glad to hear it. Faeries are a sensible option on account of the social distance. You won’t ever have to get too near.” She leans in closer, nods with her chin at the vast and lavish Manor House nestled regally within a semicircle of poplars. “Manor children observe you dancing in the distance. Flitting through sunset dappled foliage.” She raises her hands and waggles sausage fingers. “You can both dance, can’t you? Never mind if you can’t, we can sort you out.”

“I dance,” said Kash.

“Excellent!” says Madame, clasping hands together at her bosom.

“The wing thing—will it hurt?”

“Full anesthetic privileges,” boasts Madame. “Never less than the best for my faery treasures. Plus, lefty food, so you won’t have to starve yourselves for those willowy figures.”

A crowd gathers, a hodgepodge mix of tall and short, fat and squat, hooked noses, flappy ears and tizzy hair.

Kash opens his mouth but before he can speak, he’s drowned out by a voice from up the back. A soft voice calling “Tell ’em about the children!”

Pearl panics as a wave of titters ripple through the gathering.

“Hush now, Marlene,” says Madame, “There’ll be plenty of time for that once we’ve gotten these new folks signed and sealed.”

Kash grips Pearl’s arm. She pats his hand. “And we will be working alongside other faery folk?”

“But of course!” Madame places two curled fingers in her mouth and whistles, long and sharp. “Nettle dear, take our two new lovely treasures—remind me of your names again, my sweets.”

“Pearl and Kash and we need to stay together—no matter what. Our home was—”

“This is your home now, darlings, and together always you shall stay! I’ll make sure we note that in the Book.”

The crowd parts amidst much shuffling and sniffling. A girl emerges, garbed in a confectionary of lace and chiffon; mincing steps, careful not to trip. She winks at Pearl. “Youse can call me Nettie. Reckon ya wanna walk or take the carriage?”

Says Madame, “May I recommend a casual stroll around the lake past the weeping willows. Take in the sights and get suitably acquainted.”

More muttering and mumbling as the crowd disperses.

“The old bag never lets me take the carriage,” says Nettie once they are safely out of earshot. “She should try walking in these stupid shoes.”

“So gorgeous,” says Kash.

“The fuckers pinch,” says Nettie, “not to mention shatter easy on account of them being glass. I still got scars from falling off the last pair.” She tugs at her hem to expose the damage. Kash bends for a closer look, but Pearl can’t take her eyes off the immense, luxurious garden vista wrapped around them like a cloak. Deep green as far as she can see, dotted with ornate fountains. Sculpted boxwood hedges, cypress trees reaching heavenward, like arrows. Occasional crumbling ruins out of place amongst such symmetry and balance.

An old man in long white robes ambles across the lawn with the aid of a gnarled staff. Vanishes into a distant copse. The lawns are amazing. Everything in this place is amazing.

“First thing to know, don’t mind the animals,” says Nettie once they’ve left the crowd behind. “Not a one of ’em’s for real. Not dangerous, all totally built for show.”

“Not real how?”

“Mechanicals,” she continues, “but you could never tell from looking. They stink every bit as much as the real thing.”

The twins nod, because if it’s one thing they are familiar with, it’s the stench of starving, feral beasts with matted fur and dirty claws coming at you once the lights are out.

But the animals gamboling on the lawns are different to anything they’ve seen; so sleek and healthy, clean and beautiful. They pause to admire two mighty loping creatures. Freeze as one tags the heels of the other till they tumble in a playful heap.

Nettie laughs. “Like kittens, really, only bigger. Black one’s jaguar, the stripes is called a tiger.”

“But not real?” says Pearl.

“Hell no,” says Nettie, slapping the air. “But they’ll still run a mile if you try to pat them. Authentic programming in memory of the beasts that once were living. Lots of things are memorial in this place.”

Kash wants to speak but Pearl gives him a nudge. First thing’s figuring where they stand. Who to trust and who must be avoided.

The list of things she wants to ask grows with every step. Lefty food? And what about the children—are they dangerous? She’s known children who would shiv you with a shard of glass for half a moldy crust, but Calvaria does not seem like that kind of place.

Nettie wipes her nose on her wrist. “Spose she’ll want me to rattle the entirety.” Takes a deep gulp of air before beginning.

“Calvaria’s what they call Italianate. You know: topiary, obelisks, orbs, columns, cones and domes. Focal points to lead the eye, providing balance and a sense of drama.” Nettie strikes a theatrical pose and rolls her eyes. “Whole thing’s inspired by the Greeks and Romans. One pinched it off the other—I can never remember which way round it goes.”

Calvaria is the neatest place Pearl has ever seen, all clean, geometric shapes and lines. Climbing roses and lilypond terraces. Marble lion’s head fountains spewing crystal water.

“And Madame Bastarache,” asks Pearl, “is she Italianate as well?”

Nettie giggles. “Lotta rumors going round about where she’s from and what she might be hiding under those skirts—if you know what I mean.”

Pearl doesn’t know, but nods. “What did Madame mean about the children?”

“Nasty little shits,” says Nettie. “Don’t go near them tis my best advice.”

Nettie’s limp becomes more pronounced as they continue. But Pearl is too distracted by a fortune’s worth of lemon trees with overladen branches to ask why. Fallen lemons unclaimed on the grass. Bunny rabbits, plump and fluffy, unconcerned by people walking near.

After an hour spent crossing vast swathes of verdant, spongy lawn and a thousand wonders, including hedge mazes and sky glistening with unnatural sheen, and miniature versions of famous structures from old magazines: Arc de Triomphe, Acropolis of Athens, Rome Colosseum, the twins are shown to a little cottage nestled amongst others. Each one different, every garden blooming with curling fronds and pudgy blossoms, thick, fleshy leaves, creeping vines in shades of green with silver-gray stripes.

“All yours,” says Nettie. “I’ll leave youse both to settle in and tomorrow we’ll get started on the training.” She spins on translucent heels and heads back along the leaf-strewn path, pausing after a few steps. “One more thing,” she calls over her shoulder, “mind you don’t get up to anything you don’t want that lot knowing about.” She nods in the direction of Calvaria’s Manor House, gives a cheery little wave and totters off.

Peapod cottage says the engraved plaque cemented to the ivy-covered wall. Small, but neat. Less pokey than it seems from the outside. The kitchen table has places set for two. A fruit basket, fresh baked loaf and cheese.

Kash lunges, tears off chunks to stuff into his mouth.

“Hell’s sake . . . use the knife!” Pearl’s mouth waters as she sits and reaches for the cheese. Their last meal had been two days back. Watery gruel bulked up with insect protein.

“This can’t be real,” she says with her mouth full. “Gotta be a catch. There has to be.”

“Wing implants.”

She nods, cringing.

“And tigers. Maybe we turn out to be their dinner.”

“This lefty food is tasty.”

“Maybe it turns into poison in our stomachs?”

Pearl shakes her head. “But why bother? They paid for us, they must want us for something.” She casts her eye over the kitchen: grainy burled wood with earthy mottling. Smooth floors of ivory painted brick. A hearth, blue and white patterned wall tiles. Dangling copper-bottomed pots and pans.

A well-thumbed book with a bright yellow cover sits, partly obscured by the basket’s rattan bulk. She tugs it free and flips through tatty pages.

“Whassat?”

“The Types of International Folktales: A Classification and Bibliography.” She holds the page up close to her face. “Print’s too small. Smells musty.”

“Like a catalogue of faeries and stuff?”

“Not really. There’s no pictures.”

He shrugs. “Somebody ripped them out, maybe?”

Closer examination reveals jagged tears in several places. She closes the book and puts it back on the table. “Kash—the mansion song we followed could only be about Calvaria.” She closes her eyes and sings:

“When we gaze in silent rapture,

On our many mansions fair;

We shall know how sweet the promise

Of a home, forever there.”

She opens her eyes. “Finney’s favorite song. Remember?”

Kash nods, his mouth too full for speaking.

After slaking their thirsts with jug after jug of water, the twins discover two identical bedrooms snuggled side by side. They take the smaller, falling asleep as soon as their heads hit pillows.

Comments

Post a Comment